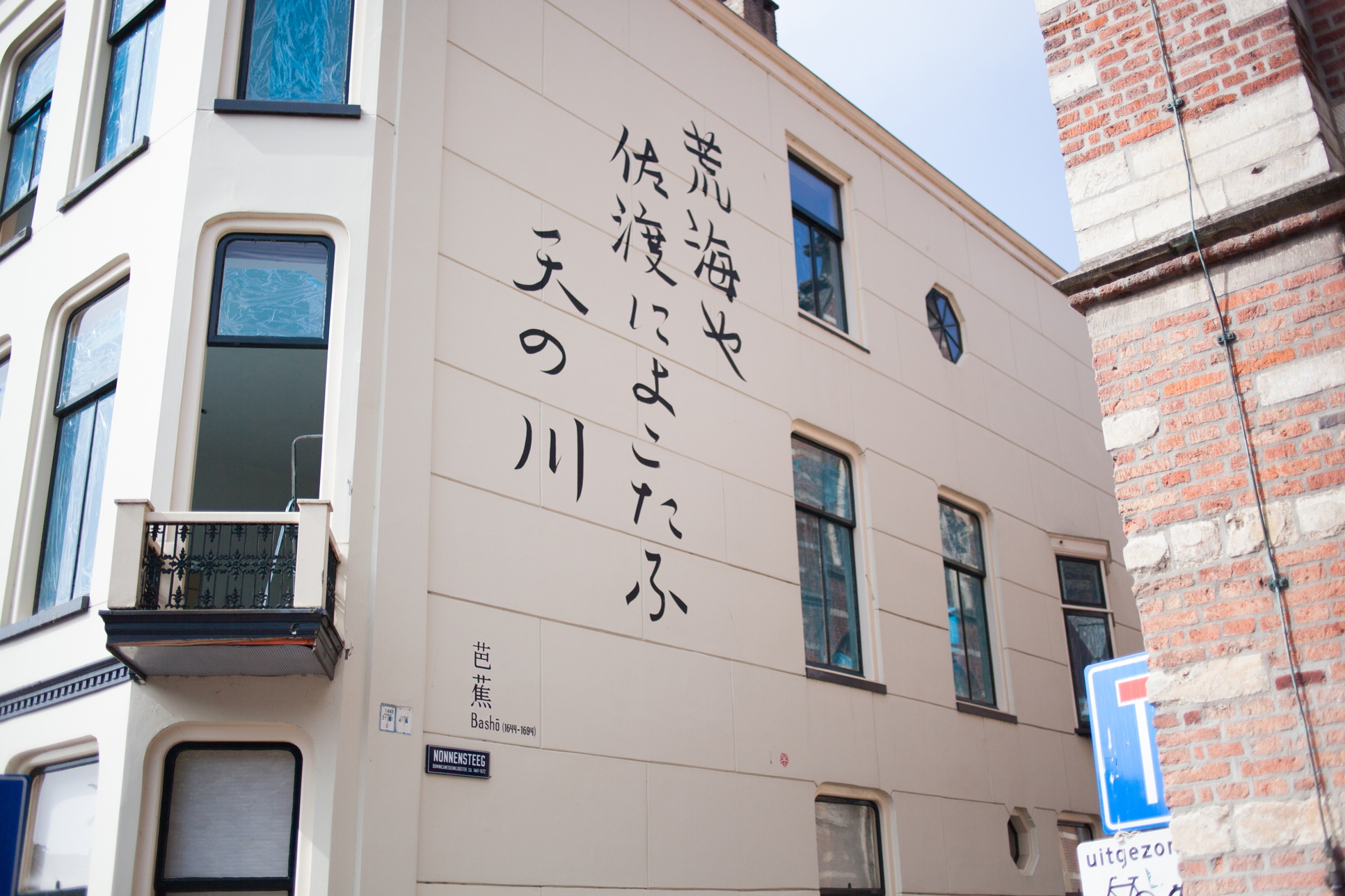

Een woedende zee!

Een woedende zee

tot aan het eiland Sado

strekt zich de Melkweg

Vertaling door J. van Tooren

Listen to this poem in Japanese.

Voice: Kiyo Fujiki

This poem in 60 seconds

On his journey through North Japan, Matsuo Bashō reaches the coastline. Before him lies the island of Sado, to which prisoners are banished. Although the island is clearly visible, it feels incredibly far away. Bashō captured the emotions he felt when gazing out the window that night in this haiku.

Want to know more? On this website you can listen to the poem, discover its origins and its author and find out what the poem means to the people of Leiden.

Over Matsuo Basho

Matsuo Basho (Ueno 1644 - Osaka 1694)

Matsuo Bashō is the pen name of Matsu Kinsaku. As the son of a low-ranking samurai, he was headed for a mediocre career in the army. This changed when he became the attendant of Tōdō Yoshitada, son of the local governor. They bonded over their shared love for haikai no renga, a type of linked verse poetry which is a collaboration of several poets. When Tōdō Yoshitada died in 1672, Bashō moved to Edo (Tokyo) to devote himself more fully to poetry.

Founder of the Haiku

In Edo, Bashō gathered fame with his travel narratives and his haiku, short verses following a strict scheme. He received thousands of pupils from all around the country and taught them not only about the technique of the haiku, but also about the frame of mind from which they originate. According to Bashō, haiku was a way of life, a state of preparedness. Prepared to take life as it comes; poverty, loneliness and all. Not free from sadness, but free from the fear of it. He instilled in his students the belief that beauty could be found in all shapes and sorts, and encouraged them to keep looking for it. To Bashō, haiku was a way of being free - from tradition, the fear of tradition and all sorts of urges. Finally, one had to be prepared to set free the fruit of years of study and preparation in just a few short verses.

A life of hardship

Bashō has traveled a lot to see the landscapes, temples and historic sites in Japan and to visit his pupils. His travel narratives - prose interspersed with haiku - contain some of his best works. He went where the clouds took him, as he said, and remained ever fascinated by “the art, to which I have devoted myself, ignorant and incapable as I may be; this is what I have chosen, above all else.” Bashō died at the age of fifty-five, on a cold winter day, exactly as he’d always pictured it.

What's this poem about?

This poem is about the moment on which, during his long journey, Bashō looks out at the island of Sado just off the Japanese coast. Leiden-based astronomist Vincent Icke, whose house has been adorned with this poem, tells us: “Sado was a prison island, rather like Alcatraz. Bashō describes how the detained are separated from the mainland by the ‘rough sea’, an unbridgeable barrier both geographically and emotionally (furious, as they were rejected by their fellow man). But they are nonetheless irrevocably connected to the free people through that band of light in the heavens, the Milky Way, which like a bridge spans the horizon.”

A long tradition

That Bashō mentions the Milky Way is no coincidence. Writer and Japanologist Jos Vos explains: “Bashō wrote this poem in the seventh month of the Japanese lunar calendar. This month is known as the ‘Month of the Poet’. The most important festival of this month, Tanabata, takes place on the seventh night. This is the only night of the year in which the ‘weaver girl’ and the ‘cowherd’ (two stars) meet, according to ancient Chinese legend. In order to reach each other, they have to breach the Milky Way.” To Leiden resident Arie de Kluijver, who did the research for this webpage, this poem describes the feeling of isolation which sometimes takes hold of him when he is far from home.

Origin story

On 16 May 1689, Matsuo Bashō set off for a long journey, accompanied by his pupil Kawai Sora. They traveled through the northern provinces of Japan in 150 days, a journey of 2,400 kilometers. Bashō published an account of this journey under the title Oku no Hosomichi (The Narrow Road to the Deep North), which also contains this poem.

The island of Sado

“On my journey along the northern coastline I spent the night at Cape Izumo in Echigo,” Bashō tells us in Oku no Hosomichi. “In the distance lay the island of Sado, eighteen miles removed from the shore, from which I was separated by the blue waves and thirty-five miles wide from East to West. So clear it was before me - even its steepest peaks and most secluded valleys - that I thought I might touch it. This island, which had carried so much gold, surely deserved to be endlessly revered, to be recognized by all the world as a true treasure. It saddens me that it has such a bad name, and that its only reputation is that of a place to which dangerous criminals and enemies of the Court are banished.”

A turbulent sea

About Sado, Bashō would go on to write the haiku that can now be found in Leiden. In his travel narrative, he explains why: “To relieve the sadness of my journey, I opened the window. The sun had already sunk into the ocean and a hazy moon had risen. High up in the sky hung the Silver Stream, the stars shining brightly, and from the open sea I heard the relentless crashing of the waves. It was as though my soul was ripped from my body and my stomach was being split open. Suddenly I was overcome by such sadness that I no longer longed for sleep. I could not fight it - the sleeves of my black robe were soaked through with my tears, I could have wrung them out.”

Share your story

Does this poem hold a special place in your heart? For example, do you remember when you first read the poem? Or did you come across it someplace unexpected? Let us know at muurgedichten@taalmuseum.nl! We would love to add your story to our website.

Bashō in Leiden

Photo Anoesjka Minnaard

Bowing for the painter

This poem was applied to the wall by Jan Willem Bruins in 1994. Bruins painted by example of calligraphed Japanese characters on paper. While he was painting, he was spotted by a group of Japanese passers-by. Filled with adoration, they stopped to watch Bruins apply the characters in a slapdash fashion. They asked if he had ever done a calligraphy course. When he said that this was his first try, they paid their respects to the painter with a deep bow.

I see a star

Leiden-based astronomer, physicist and artist Vincent Icke choose to adorn his home with Bashō’s haiku. Icke designed his own signature, which bears resemblance to a Japanese cherry blossom. This flower is often used in Japanese sigils. The image combines Icke’s initials, V and I, to form a star shape at the core of the flower.

Bashō and haiku

Bashō is known as the founder of the haiku, a form of poetry which employs the 5-7-5 rule: 5 syllables in the first line, 7 in the second and 5 again in the third. In Japan, the haiku is often noted as a single vertical line, on which the trichotomy is subtly visible. Generally, these spaces are also marked with a so-called ‘cutting word’, or kireji: a particle with no semantic meaning, but with a strong influence on the connotative value or overall tone of the poem.

Haikus are often about nature and eschew value judgements. They generally do not rhyme; rather, they contain more subtle plays on sound, such as the repetition of consonants or vowel sounds. These days, this form of poetry is practiced in many countries and languages around the world. Some Western haiku poets conform very strictly to the traditional Japanese model while others, even within Japan, deem it unnecessary to cling to these rules when writing in a different language.

Popular Japanese poetry

Bashō and his haiku are incredibly important in Japanese culture. The Dutch pioneer in haiku, J. van Tooren, wrote: “Poetry is popular in Japan; its popularity is at a level we can scarcely imagine. Almost everyone occasionally puts some words on paper, they know and read the greats, and the recognition, the appreciation for poetry is widely shared among the population. This is partially due to the nature and history of Japanese verse, which from its very onset has never been about an exclusive expression of the poet’s own personality, but about conveying, in simple yet harmonic form, his experience.”

Quotes

Bashō’s influence is beyond measure.

Miyamori, writer of the standard reference work An Anthology of Haiku Ancient and Modern

Do not seek the footsteps of the wise. Seek what they sought.

Matsuo Bashō

Fun facts

- Bashō means ‘banana tree’ in Japanese. When, in 1680, Bashō decided to retreat and live life secluded as a hermit, his pupils built a him a hut. In front of it, they planted a banana tree. When the poet took up residence here, he also took on the name Bashō.

- From the seventeenth century, the term haikai (short for haikai no renga) was used for the experimental poetry of the samurai, merchants and the nobility. Like the upper classes, Bashō and his students also wrote linked verses, though unhindered by the sophisticated constraints of the aristocratic poetry.

- The word ‘haiku’ first appeared towards the end of the nineteenth century - centuries after Bashō’s death. The word haiku is derived from hokku, the opening poem in linked verse poetry that follows the 5-7-5 pattern. For this type of verse, the Japanese poet Shiki coined the term ‘haiku’. Almost all of Bashō’s hokku were part of a linked verse, which a group activity par excellence. However, even in the seventeenth century, hokku were considered suitable for stand-alone enjoyment as well. In his travel narratives, Bashō incorporated dozens of hokku.

- The first westerner to ever try his hand at haiku was a Dutchman. Hendrik Doeff, governor on the Dutch trade isle of Dejima, off the coast of Nagasaki, wrote what is thought to be the first non-native haiku in 1819.

- Bashō wrote this poem on the day of the Tanabata festival. In Japan, this festival is still celebrated today. People decorate their homes with long bamboo shoots, to which colorful strings of paper are tied on which people write short verses or good wishes.

Lees dit gedicht in het Japans

荒海や

差渡によこたふ

天の川

---

Ara umi ya

Sado ni yokotafu

Ama no gawa

Dit gedicht is op muziek gezet door de Leidse band Street fable.

The rough sea

The rough sea -

Extending toward Sado Isle,

The Milky Way

Translation by R.H. Blyth

Learn more

This entry was written by Taalmuseum in collaboration with Arie de Kluijver. The translation into English is by Anne Oosthuizen. The following publications were consulted:

- Matsuo Bashō, De smalle weg naar het verre noorden; Gekozen, vertaald en ingeleid door Jos Vos (Amsterdam 2011)

- J. van Tooren, Haiku een jonge maan (Amsterdam 1973)

- Haiku.nl